A Chance to Start Anew.

Thank goodness 2020 is behind us. As we enter 2021, if tradition holds, a new president will be sworn in at noon on January 20th.

This event should be celebrated by all Oak Ridgers for a small, but very important reason. With a new administration, the nomination of Ed Westcott to be awarded The Presidential Medal of Freedom can be resubmitted to the White House.

This would be round two for the nomination. In 2017 Rep. Chuck Fleischmann and Senator Lamar Alexander submitted the nomination of Ed to the White House. The nomination was problematic from the start. President Trump is a transactional politician. In 2016, Trump won Tennessee by 26 percentage points. There was no upside for Trump to give the award to Ed.

Rep. Fleischmann didn’t have enough pull in the Oval Office, so the nomination gathered dust in somebody’s desk drawer. Sen. Alexander didn’t endorse Trump in 2016, so even more dust gathered. Trump, evidently, was in no mood to do favors where he did not directly benefit.

As the White House changes administrations, the dusty Westcott nomination is in a huge trashcan somewhere, waiting to find a final home in a landfill on the outskirts of Washington, D. C.

All nominations are problematic. A second Westcott nomination would be no different. Rep. Fleischmann could sponsor it again, but circumstances have changed. Fleischmann signed onto the effort by the state of Texas to have the Supreme Court overturn the election results in Wisconsin, Pennsylvania, Michigan and Georgia. He won’t be getting a Christmas card from the White House this year. Rep. Burchett won’t be getting a Christmas card either. He signed onto the attempted judicial coup too.

Sen. Blackburn doesn’t have much pull in the Biden White House. Senator-elect Hagerty might be a wild card, in a good way. He lived in Japan for a total of five years on two separate occasions. Hard to know if he would support or oppose a Westcott bid. He was Ambassador to Japan for two years.

Oddly enough, retired Sen. Alexander might play an important role this time around. He and Biden were in the Senate together for six years. Alexander has said nice things about Biden on the floor of the Senate. I certainly understand it is a very long way from complimenting a vice-president to asking a president for a favor, but compliments are a good start. If Alexander could get one or two Democratic Senators to co-sponsor the effort, the odds of an award increases too.

The unknown in all this is what Biden believes about Hiroshima and Nagasaki. In most public surveys about the bombings, Republicans (74% Pew survey 2015) generally support the decision to use the atomic weapons more than do Democrats (52% Pew). Biden would certainly get criticism from the left wing of his party for a Medal of Freedom award.

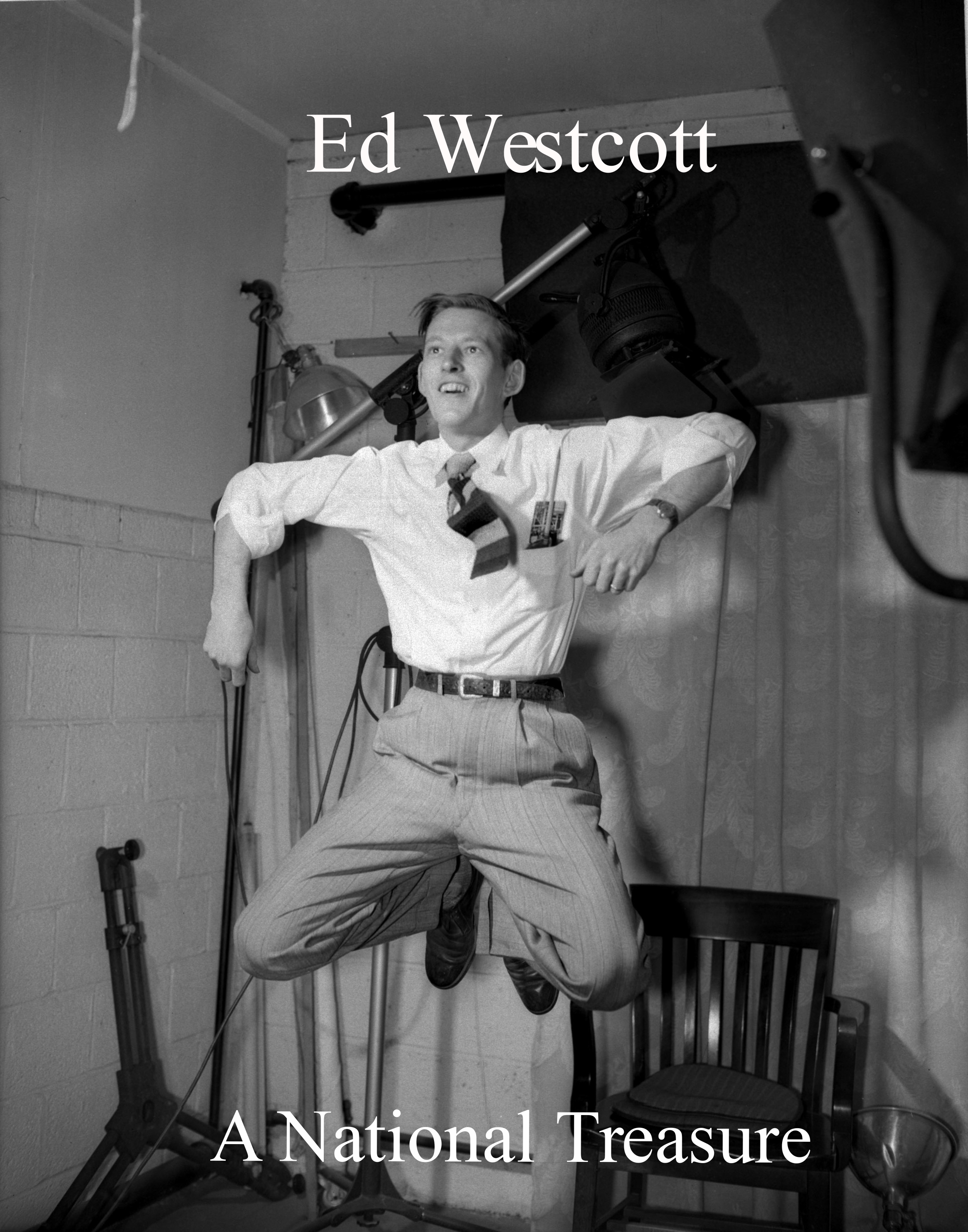

Ed has earned this award. As a 21 year old he tackled the job of recording the most important event of 20th century American history. He completed the most important photographic archive of our nation’s history before he was 24. The last photographer to win the Medal of Freedom was Ansel Adams in 1980.

It is time for Westcott to take his place with Adams. He has been ignored far too long. The only question is if we have a president-elect who can make the decision. I hope we know the answer very soon.

Ed Wescott deserves The Presidential Medal of Freedom

A small movement has been started by citizens in East Tennessee to have photographer Ed Westcott awarded The Presidential Medal of Freedom. It is the United States' highest civilian award. The last photographer to be given the award was Ansel Adams in 1980. Ed Westcott created the most important photographic archive of 20th century American history. He has earned this award many times over.

A YouTube grass roots movement

On April 21, 2020 I posted a video on YouTube about Ed’s work and his nomination. People can share the video on social media. With enough “views” say 50,000 or so, the news media will see it at as a legitimate news story. Here is the link to Ed’s video.

Sign a petition supporting Ed’s nomination

Janie Fox took the bull by the horns and created a petition to support Ed’s nomination at the website change.org. Here is the link to the petition. Encourage your family and friends to go to the link too.

One step closer

According to the office of Congressman Fleischmann, Ed Westcott's nomination for the Presidential Medal of Freedom was forwarded to the White House last June. Even though Ed is 96, I guess there didn't seem to be any hurry to announcing the nomination. Yikes. The Knoxville New-Sentinel had a story about the nomination a few days ago.

I guess if Ed wins the award, it won't be announced until his funeral.

Trying To Move The Needle A Little Bit

Saturday, July 27, 2019

Ed Westcott died in March at 97. He should’ve been awarded the Medal of Freedom while he was alive, but the movers and shakers in East Tennessee couldn’t or wouldn’t get it done. A tragedy of the deepest order.

I am not one of the movers and shakers in these parts. On occasion, I cross paths with the powerful and the rich and I always ask for an update about the award. The answers are almost always the same: deeply condescending and vague. They assure me they know how to work with the powerful and the important and that it takes time. I feel like they want to pat me on the head a tell me not to worry my little noggin over it. They have totally failed to get Ed the honor he deserves and the movers and shakers are pretty damn cocky about their failure. A tiny bit of humility would be welcome.

In a few days a digital billboard in Solway will urge President Trump to award Ed Westcott the Medal of Freedom…RIGHT NOW. Perhaps it will shake the media tree a tiny bit. Here’s hoping.

Script for a history podcast about Ed.

In August of 1934 President Hindenberg of Germany died. Chancellor Hitler moved quickly to consolidate the office of President and Chancellor and molded it into a new position as dictator. His new title was Führer. A national referendum weeks later was approved by 90% of the voters. It was a mere rubber stamp of what Hitler had already done by fiat.

Meanwhile in Nashville, Tennessee Ed Westcott’s father, after saving for a year, bought 12 year old Ed his first camera. It was a German made Foth Derby. They found a used mobile lunch wagon which they renovated into a darkroom. Family, friends and neighbors could get film developed for 50 cents a roll. A photographer and an entrepreneur was born. He was largely self-taught. He started working with portrait studios in Nashville, while still a teenager. He had ambition but he also had hustle.

There were clues in east Tennessee in September of 1942. A press release published in newspapers said the military was building an ammunition testing range outside of Knoxville, Tennessee. This partially explained the huge condemnation of 58,000 acres by the government, The reports in newspapers were a total lie. The true purpose of the seizure couldn’t be revealed.

Farmers who owned the land were totally in the dark. Surveying crews asked permission to be on their land for a few hours. In November owners found a single piece of paper attached to the screened front door announcing that the owners of the land, had three weeks to vacate the property. It was being confiscated by the federal government. Just imagine trying to get out of your home in three weeks. Many of these families had farmed their land for generations. The farm houses were bulldozed down in a matter of days after the eviction date.The ammunition testing range excuse was done on purpose. It discouraged squatters. It worked.

The families viewed their farms as a Utopia, a personal Garden of Eden. The land provided for all their needs, both physically and spiritually. For many their Garden of Eden had been in the family for almost a 100 years. Most families never, ever got over the quick harsh eviction. They were compensated for their land, but hundreds of farmers were looking for new farmland at the same time. Prices went through the roof. Many of the farmers ended up working at the industrial plants which were built on their former land. In many instances they prospered financially. But still, decades later the sting of betrayal did not fade.

Meanwhile, 160 miles to the west, in Nashville, a 20 year old man, had a decision to make. Ed Westcott was a photographer for the Nashville office of the Army Corp of Engineers. The office was being closed. Ed was offered two options: He could transfer to the Alaskan highway to document the construction of it, or he could go to a new installation outside of Knoxville. Ed had spent all of his entirely too brief life in Tennessee. He recently got married and had a new born son. Not a good time to head for the wilds of Alaska.

Knoxville it was. He accepted the job in November and would start in January of 1943. His employee number was 29. Little did he know that in less than three years, he would create the most important photographic archive of 20th. century American history.

Ed said there wasn’t much going on when he reported for work. Putting in roads and rail lines was the first order of business. Ed said if this was a war project it wasn’t much of a project. That would change quickly.

Ed dove into his work. From January 1943 until the end of the war in August of 1945 he took 15,000 to 20,000 photographs. In an era where everyone has a camera on their cellphone. that doesn’t sound like much: really: 16-21 photos every single day, but it was a different time. The cameras were heavy and often he needed heavy tripods to mount his camera on. During the war Ed had a 4x5 Speed graphic which used roll film with six exposures on each roll and then he had an 8x10 Deardoffer which used a single sheet of film for each photograph. If he was shooting inside he had to use bulky flood lights which took a long time to set-up, often times for just a single shot. And at the end of the day, he had to go back to his darkroom and develop the day’s film and print proof sheets. Then, there might be a dance to shoot later that night.

Cameras were banned in the secret city. His was the only camera in a town of 75,000 and for a guy with ambition, his side hustle as a photographer was almost a full time time job on its own. There were many weddings each weekend. Ed was, literally, the only photographer in town. Babies were being born left and right. The fastest growing department at the hospital was the maternity ward. If you needed photos of your first born, Ed was the man.

The speed and scale of Oak Ridge was unlike anything the country had ever seen. From the time the farmers were evicted until the day Japan surrendered was a mere 1,020 days. This top secret installation went from cows grazing pasture land, to the 5th largest city in the state, and one of the largest industrial complexes in the history of mankind.

Splitting an atom was an astonishing new energy source. Think of taming the power of fire. Or perhaps inventing the wheel. Atomic energy had the potential to transform the world. It was the most important discovery of civilization. It was fully realized in Oak Ridge, Tennessee.

Fission can be used in a tightly controlled way to produce electricity in nuclear power plants. Or, the process can be done not in a controlled way, but in a totally uncontrolled way, where all hell breaks loose in a millionth of a second. A thought experiment. Let’s look at days as opposed to seconds. How far back do you need to go to embrace a million days? How about 717 BC?

Timing, both good and bad, can be a terribly random thing. In December of 1938 two scientists in Germany discovered a uranium atom could be split and release a massive amount of energy.

Barely eight months later, Germany invaded Poland and World War II started. Nuclear fission, because of the war, would be weaponized first. The first perception of atomic power by the world would be during war. At Hiroshima 60,000 people died in a tiny fraction of a second.

General Dick Groves ran the Manhattan Project. He was a no nonsense, impatient taskmaster. His second in command was Col. Ken Nichols. They were hired in September of 1942.

Things happened quickly. They made the decision to step up the process to condemn 60,000 acres of farmland west of Knoxville, Tennessee. They also obtained from the War Production Board a AAA priority rating, it was the highest rating possible. There were shortages of thousands of materials during the war. The Manhattan Project would be first in line for anything and everything. This was huge. Another objective was to “borrow” from the US Treasury 14,000 tons of silver for the industrial plants in Oak Ridge. That is the weight of 9,000 cars. The Pentagon, one of the largest office buildings in the world, has 8,700 parking spaces.

They also contracted with a uranium mine owner in the Belgian Congo for 1,250 tons of high-quality uranium ore.

Impressed? You should be. Dick and Ken completed these four vitally important objectives during the first four days on the job

The scale of the project was unprecedented in human history and

the speed of it reads almost like science fiction. In 18 months they built the fifth largest city in the state. They built 3,000 homes. During the peak, a home was completed every 30 minutes.

There were over 6,000 massive industrial machines separating isotopes of uranium. These machines were energy hogs. Oak Ridge devoured 10% more electricity than New York City during the war. New York had over 7.5 million residents. Oak Ridge? 75,000.

For safety reasons, workers lived miles from the industrial sites. These were new, experimental processes creating a new type of uranium. There were worries an accident would be catastrophic. To ferry workers to and from the plants, they built the ninth largest bus system in the country. A bus arrived or departed from the main terminal every 60 seconds 24 hours a day, seven days a week.

Even with the industrial plants the speed of construction was head-spinning. There were three different ways to separate uranium-235 from its worthless cousin uranium-238. The problems were huge. For every 2,000 pounds of raw uranium there was only 14 pounds of the precious uranium-235. Separating the two was one of the most significant events in the history of mankind. The plants were named S-50, K-25 and Y-12. The names were total gibberish. They were created to make sure absolutely nothing was conveyed to the workers, and the outside world, about the purpose of these plants.

Even the path from laboratories to massive industrial plants was abbreviated. Normally after a theory is proved in the laboratory, a prototype is build to see if the idea is scalable. There was no time for that. K-25 used a filter method. There was a 2% difference in the size of uranium-238 and the smaller uranium-235, the one needed for a weapon. A filter would have holes small enough that the larger 238 could not pass through, but the smaller 235 could. A filter the size of your thumbnail would have over 15 million holes in it. When they started building K-25, the scientists had not developed a filter which worked. The scientists just kept grinding out possible solutions until they developed one which worked. Much of what happened in Oak Ridge was based mostly on blind faith.

Why such a rush? Why the obsession with speed? Only people in the highest echelons of the military, government and science knew the horrible secret which kept all of them awake at night.

Hitler had his own atomic weapons program. As with our program, it was top secret. We knew almost nothing about it., but what was known was nightmarish. Hitler had a two year head start.

This was the original arms race. If Hitler got the weapon first London would be gone. Moscow most likely too. Perhaps Leningrad. Millions of people would die. If Hitler could get an airfield in Greenland, the entire east coast of the United States would be under threat. At the very least, all of Europe and Russia would be under Nazi control. The resulting carnage would make The Holocaust look like a very tiny blip on a moral radar screen.

There were 75,000 workers in Oak Ridge. Only 200-300 workers knew the purpose of the this giant industrial site.

But all the workers were highly motivated to end the war. They had family and friends dying in distant lands. The loss of American life during World War II would equal a 9/11 attack every five days for 3 1/2 years.

From the bottom up workers were pleading with their bosses

“What can we do to end the killing?” And from the top down the leaders did their own pleading, “Faster. Work faster.” Forces from the very top of the Manhattan Project and the fears of workers on the bottom rung of the labor pool all came together in Oak Ridge, Tennessee unlike anywhere else in the nation.

This is not an extraordinary Oak Ridge story at all. There are dozens of stories like this one.

Professor Alden Blankenship was a professor of education at Columbia University in New York City. In late June of 1943 an Army officer scheduled an appointment. When he arrived, he told Alden that he couldn’t tell him much, but everything he told him was confidential. The Army was building a town from scratch for the war effort. The officer could not tell him where the installation was or the purpose of it.

The army needed to build the infrastructure for a school system. The army had no interest in running the schools. They needed to hire a superintendent for a school system. He had come highly recommended. There would be children of scientists and engineers in the schools. The parents would demand excellent schools.

The opportunity to start an entirely new school system was extraordinary. No inherited problem employees. No unwanted programs which were politically impossible to disband. No mini-fiefdoms among staff members to contend with. Not even problem students or parents, well not at least, at the start anyway. It was stressed that he would be making an important contribution to the war effort. Blankenship was tempted, but he had a young family and uprooting them would be a difficult decision.

Blankenship said he needed to think about it. When did the officer need an answer. The officer looked at his watch and said, “Four hours.”

Blankenship stepped out of a car in Oak Ridge nine days later. It was July 10th, 1943. As he wrote later, he was the new superintendent. He had no office, no schools, no materials and no staff. Yet, in October of 1943 schools opened. There were three schools, staff and 637 students. It had taken 87 days. By the end of the school year there were over 4,000 students and a year later there were 11,000 students.

The schools reflected the growing pains of the larger community. The first official estimate for the population was 12,000 residents. Then it was revised to 25,000 then 45,000 and the final guess was 65,000. It peaked at 75,000 people.

One worker said that everything and everybody was going at a full gallop all the time. The workers were told what they were doing was important war work. And they believed it. They believed it because the evidence was all around them. The officials kept the purpose of this place secret, almost against all odds. But there were two aspects of the top secret project which could not be hidden from the workers.

One was the scale of what was going on. Nobody knew what it was, but it was the biggest effort they had ever seen in their young lives, and it would be the biggest effort of their entire lives. There would never be a more important project in their professional lives.

The other aspect which could not be hidden was the speed of the effort. Everyone could see it was moving at a blistering pace. It seemed that housing and industrial plants were built almost overnight.

Those two elements speed and scale made the atmosphere electric. Throw into the equation youth and hormones and it was the most amazing place in the country. The workers say it was the most exciting time of their lives and the scariest too. The terror and carnage of war was the backdrop for everything.

Officials in Oak Ridge were amazingly successful in keeping the purpose of this industrial city secret. You can’t hide a town of 75,000 people.

But what was going on out there, folks in Knoxville wondered. In other military plants the narrative was straight forward. Thousands of rail cars of raw materials would be shipped in and thousands of jeeps or tanks would come out, sometimes on the same flatbeds which brought in the raw material. Or the locals could see thousands of newly finished planes taking off. No mystery at all.

Oak Ridge was different. Thousands of rail cars delivered raw materials and nothing, absolutely nothing was coming out.

Well, something was coming out, but nobody saw it. It was a single piece of a grey looking metal the size of a volleyball. It was made up of 90% of uranium-235. Not thousands of volleyballs, but a single one. Over 75,000 workers were working desperately around the clock making a volleyball. And if they could make one, they might be able to make a second one. In 2020 dollars, they would spend $14 billion on a single 140 pound volleyball.

Of course, if this was a Hollywood movie, the entire volleyball would be delivered to Los Alamos, New Mexico in a security convoy. It didn’t happen that way.

As enough uranium was separated a military officer, dressed in a business suit would be given a sealed briefcase. Inside the lined case was two teacup sized containers with screw lids nestled in a special carrier. The officer would go to Knoxville and get on a public train and travel to Chicago. At the train depot he would meet another officer dressed as a business man who would take it and get on a train bound for Albuquerque and then he would drive to Los Alamos. The officer going to Chicago from Oak Ridge never knew where the briefcase was going and the other officer never knew where the briefcase came from.

When workers went to Knoxville to shop or eat, they were trained how to answer questions from nosey natives.

What are you making out there?

85 cents an hour.

What do you do out there?

Project management

How many people work out there

About half of em

The obsession with secrecy and security was well founded. Officials were deeply concerned that the Germans would learn the extent of the American efforts and would double down on their own program. Or, more likely, the Germans would infiltrate Oak Ridge and steal industrial secrets about American methods to aid their own work.

When all workers were hired in Oak Ridge they went through an 8 hour orientation. Six hours of it was: keep your mouths shut. Don’t talk about your work to anyone, including your spouse. You could be fired and possibly go to prison for espionage. There were billboards everywhere in town which said, “shut up and do your job.” Every six months there was a refresher course in case you didn’t get the message the other four times. Out going mail was opened, read and portions were blacked out if necessary.

One of the tragic unintended consequences of these dictates was that nobody kept diaries or journals. Workers were petrified that military police would find them if they searched their homes. Oral histories done decades after the war will be the only record of the memories of these ignored heroes.

There was something very conflicted about working and living in Oak Ridge during the war. At work, there was little to no job security. There were prohibitions, procedures, protocols and security standards. Asking too many questions was a sure way to be fired. Of all the people who left the Manhattan Project, 40% were fired. You were a very tiny cog in a massive machine.

Officials were greatly concerned that the workers would up and quit in droves. They were all strangers. Many of them were away from family and friends for the first time. The secrecy grated some. All the rules at work put strains on some. Military spies, posing as workers, were planted in the industrial plants to make sure security wasn’t breached for any reason. Sometimes, co-workers just simply disappeared. The mythology was that they were re-assigned to a radar tracking station in Alaska. You didn’t dare ask about workers who disappeared. It would bring you unwanted attention.

Outside of work, officials were determined to keep the workers happy. To the extent possible, the workers were pampered. Movie theaters were packed. Dance halls were full. Because most of the workers were working rotating shifts each week, athletic leagues competed around the clock. There was a symphony orchestra made up of volunteers.

A playhouse was opened which is still in operation today.

If you wanted a special interest club for a hobby, you would tell authorities and they would do the publicity. At one time, there were eight different Orchid Clubs.

Ed Westcott created a vivid record of the social history of the town. He took thousands of pictures of the industrial plants. Honestly, these are photos only a scientist could love. A machine is a machine. But photos of folks living their lives was where Ed’s talents really came to the fore. Those photos tell a human story and Ed was a master at that part of the story.

There was a sense of expectation in the summer of 1945 among some of the Oak Ridge workers. Some workers got a heads up from their bosses. Something was a foot. Husbands told their families to keep their radios on. They didn’t say why.

Certainly Ed Westcott knew something was up. It was toward the end of July of 1945 and he was instructed to print hundreds of copies of 18 of his photographs for press packets to be sent to hundreds of newspapers across the country and even foreign newspapers. He printed THOUSANDS of photographs.

Ed had in the last few months pieced together what was happening in Oak Ridge. He went everywhere and saw almost everything. He wasn’t totally sure, but he was mostly sure. He had a hunch.

In late August of 1945 he was sent rolls of film from military photographers in Hiroshima and Nagasaki. He was the only one allowed to develop the film and print the photographs. It took him three days. Armed guards were posted outside his darkroom door the entire time.

President Truman gave a mid-day address to the nation on August 6th of 1945. He revealed that the United States had developed a devastating new weapon called an atomic bomb. They had dropped an atomic weapon on Hiroshima, Japan. It was equal to 20,000 tons of dynamite.

Almost as an aside, Truman said the weapon had been developed in Pasco, Washington in Los Alamos, New Mexico and in Oak Ridge, Tennessee outside of Knoxville. That is how almost all the workers learned about what they had been working on. From the President of the United States on the radio.

Hugh Barnett joined the Manhattan Project while its offices were actually in Manhattan, in New York City. He learned the purpose of the Manhattan Project his first day at work. He moved to Oak Ridge in 1943.

In the summer of 1945 it was obvious to Hugh that the project was closing in on the amount of uranium-235 they needed for a weapon. He car pooled out to K-25 each day with four other workers. They all knew the purpose of their work in Oak Ridge. They had an informal betting pool about what date the bomb would be dropped.

August 14th was Hugh Barnett’s 29th birthday. Hiroshima was bombed on August 6th and Nagasaki on August 9th. The entire country was on pins and needles, expecting the surrender of the Japanese. Hugh was not celebrating his birthday that day. But he was also on pins and needles too. His wife Shirley had gone into labor with their first child.

They were at the hospital. It was three blocks from the main townsite called Jackson Square. There was no air-conditioning, so the windows were open to fight the intense summer heat. Hugh’s first son was born at 7pm. The commotion in the hospital room subsided, but Hugh and Shirley could hear distant cheering outside their room. Hugh wondered how word had spread so quickly about the birth of Lee.

President Truman in a nation wide radio address at 7pm announced Japan had surrendered and that World War II, after 65 million deaths, was finally over. There was great joy in the hospital room that night and in the entire nation too.

Meanwhile, in Jackson Square, three blocks away, Ed Westcott was taking photos of Oak Ridgers celebrating the ending of the war. There is a famous photograph of a huge crowd celebrating, looking directly at Ed who was standing in the bed of a truck. Many held up the Knoxville newspaper with a half page headline which shouted out WAR ENDS. With that photo Ed Westcott must have wondered what the future held for him. His job assignment was essentially done. With that photograph, Ed had brought to a close the most important work of his professional life. On that night he finished the most important photographic archive of 20th. century American history. On that night Ed Westcott was 23 years old.

As it turned out, Ed stayed in Oak Ridge as a government photographer for another 20 years.

In 2017 he was nominated for the Presidential Medal of Freedom, our nation’s highest civilian honor. The last photographer to be given the award was Ansel Adams in 1980.

In 2016 the HonorAir program in Knoxville, which is 25 miles from Oak Ridge, decided to expand their definition of a veteran to include Manhattan Project workers who worked in Oak Ridge.

The program flies over 130 veterans each trip to Washington DC to tour the war memorials. The trip is done at no charge to the veterans. They leave in the morning and are back in Knoxville the same evening. It’s a long day for all the veterans and the volunteers who make it all possible.

In October of 2016, four Oak Ridgers took the trip. Among them was Ed Westcott. I was not there for the send-off, but I was there that evening for their welcome home, along with thousands of other people. Days later, my impressions were printed in a local paper.

An American Icon Goes on an

HonorAir flight to Washington, D. C.

The old man was part of a very long parade, from the terminal hub, down the long sloping ramp to the main lobby of the airport.. He blended in. He looked grizzled and worn. He was being escorted in a wheel chair.

More than 130 veterans from what seemed lie long ago wars to many Americans, were coming back from a day in Washington D. C. Long forgotten wars to many, they were very much alive in the hearts of these now elderly men, who suffered for their country horrors beyond imagination.

The ramp was packed with screaming, cheering, clapping, flag waving Americans of all ages. These heroes made their way down the ramp without fanfare for themselves. They were modest. They were happy about the adulation, but strong emotions were being held in check. They wer grateful for this heroes’ welcome, but were obviously over-whelmed a bit at their reception too.

Like many veterans, the old man in wheelchair had an electric smile, his eyes ablaze with wonder at this welcome. He took it all in. His son-in-law steered the wheelchair, negotiating the ram and the crowd, which allowed only a single line of heroes at a time. Celebrants were five deep on both sides. The line moved slowly.

No one knew who that old man was in the wheelchair. It mattered not to the crowd. This was a veteran on an HonorAir flight. For the celebratory congregation of patriots that was enough.

The old man was a photographer. In fact, he was the official photographer for the Manhattan Project in Oak Ridge during World War II. He was hired in November of 1942. On August 14, 1945 he photographed Oak Ridgers celebrating in the town square after President Harry Truman announced on the radio that Japan had surrendered and had told the nation that World War ii, after 65 million deaths world-wide, was finally over.

Ed Westcott was the photographer. On that summer evening, 71 years ago, his work was mostly done. During those two and a half short years he had taken more than 20,000 photographs. He had created the most important photographic archive of 20th. century American history. His body of work would be unrivaled in the American experience. In August of 1945, Ed was 23 years old.

Now he’s 94. He’s going down the long ramp at McGhee Tyson Airport, receiving the praise of people who have NO idea they are meeting a pivotal figure of the Manhattan Project. It mattered not. To all who are there, these senior citizens are iconic American heroes.

I watched him as he passed and headed down the ramp into a solid wall of gratitude. He weakly raised one hand to wave to the crowd. I could see the back of his head only, as he was disappearing into a sea of faces, all lit up, all smiles, all their hands reaching out to touch his shoulder, or reverentially clasp his hand. Over the roar of the high school marching band, folks leaned in close and shouted their gratitude to a total stranger.

It had the feel of religious piety. It was visceral. It sent a shiver down your spine. This loud boisterous crowd felt they were part of something much larger than themselves. These veterans, many of them very old, were treated like holy men. To touch them and to look into their eyes was to be bestowed with a sacred benediction.

Slowly, he and his son-in-law made their way, eventually getting swallowed up in an emotional avalanche of smiling, beaming faces and outstretched, urgent hands. People desperate for a touch and a smile: needing to make a connection with our American past and needing to express their personal gratitude. None of them knew they were meeting the most important photographer of 20th. century American history.